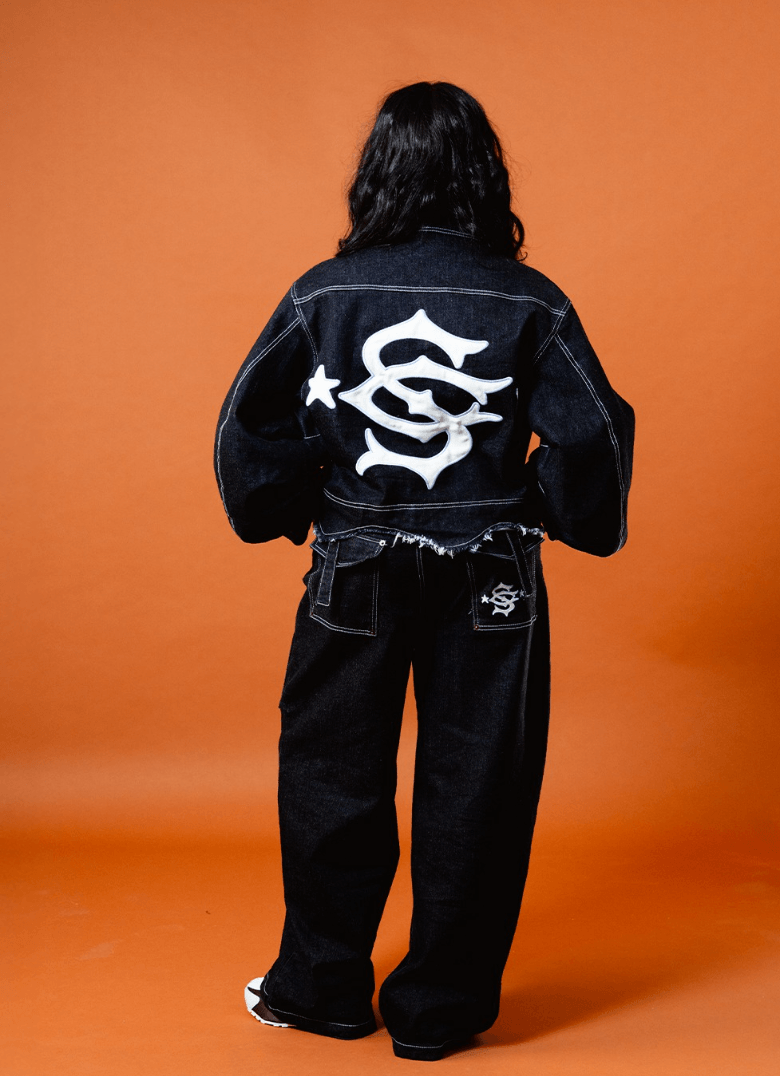

Bree Street Picnic: Reimagining the Streets

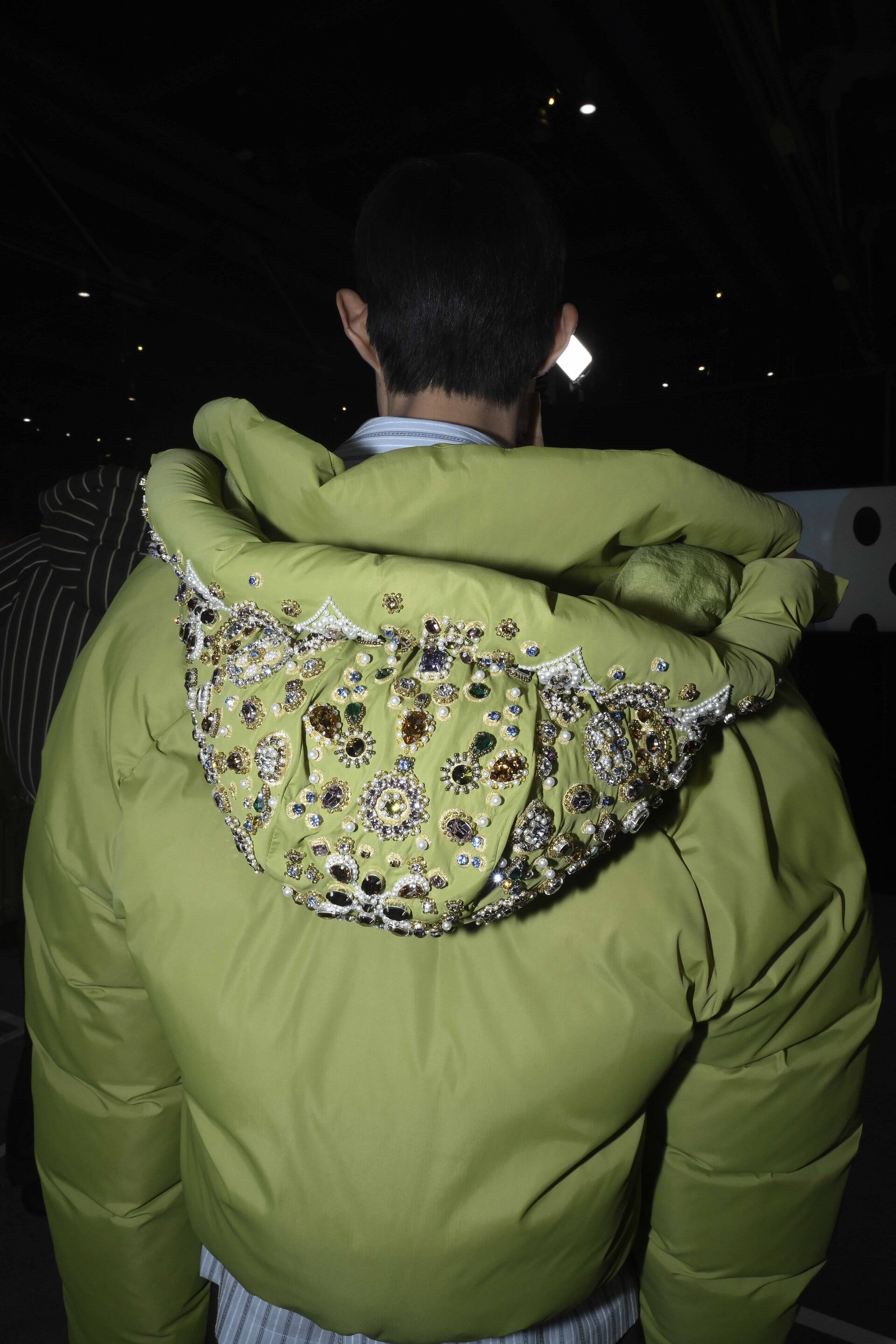

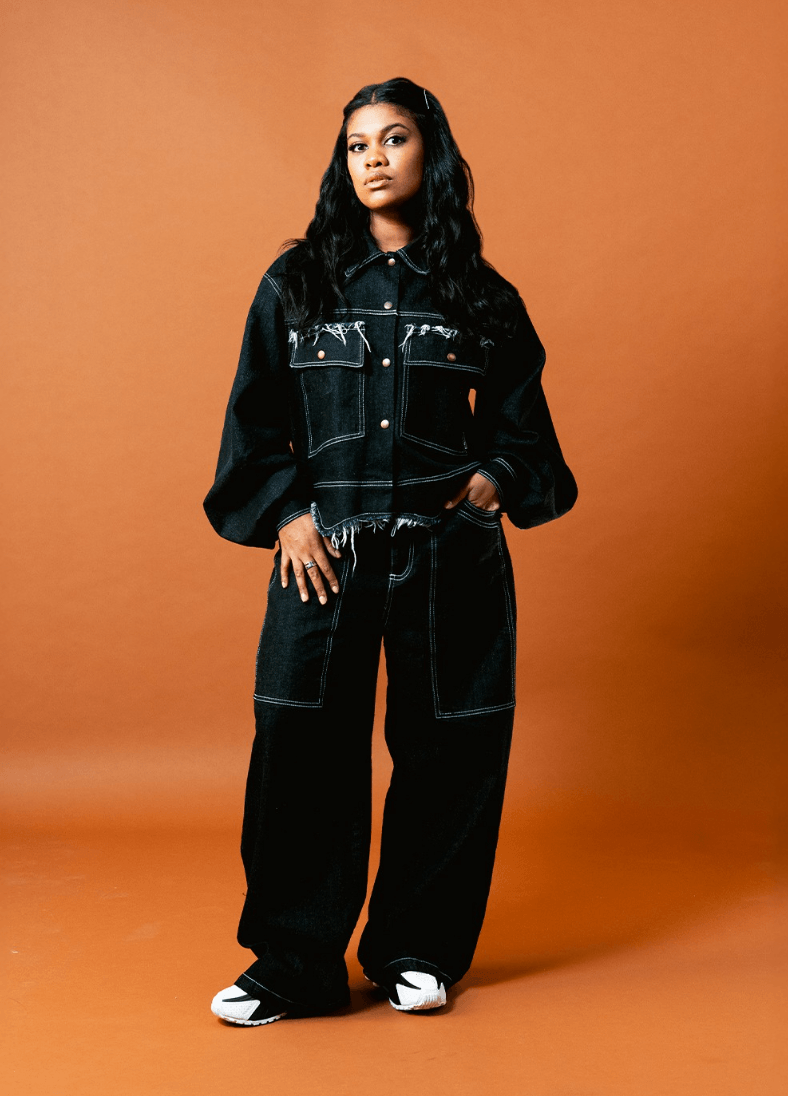

The Bree Street Picnic is part of an ongoing research and public art project that explores collective-making as a tool to grow community and activate public space. Over the course of 2 months, volunteers joined public sewing workshops and donated fabric to complete giant picnic blankets. Each blanket contributes to a growing collection of ‘soft public infrastructures’ that are prompting questions around how to make cities more human-centered, welcoming, comfortable and fun.

“For cities to evolve, they require programming that helps people think differently about how we define and use public space. The Bree Street Picnic Blanket meets this brief and is a good example of how to unlock the public potential of our streets.” Shares Roland Postma, of Young Urbanists.

Imagery courtesy of Picnic and The Maak

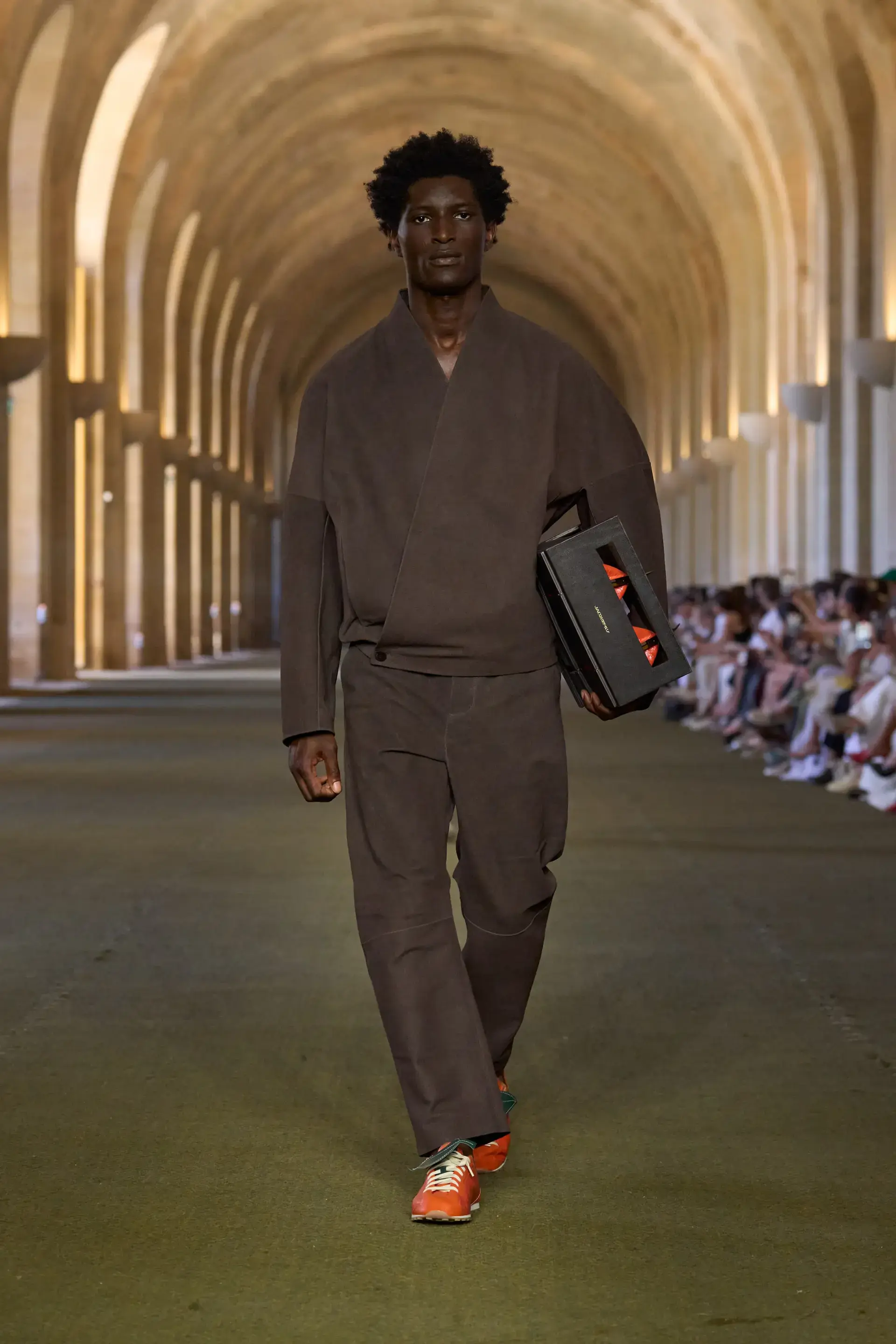

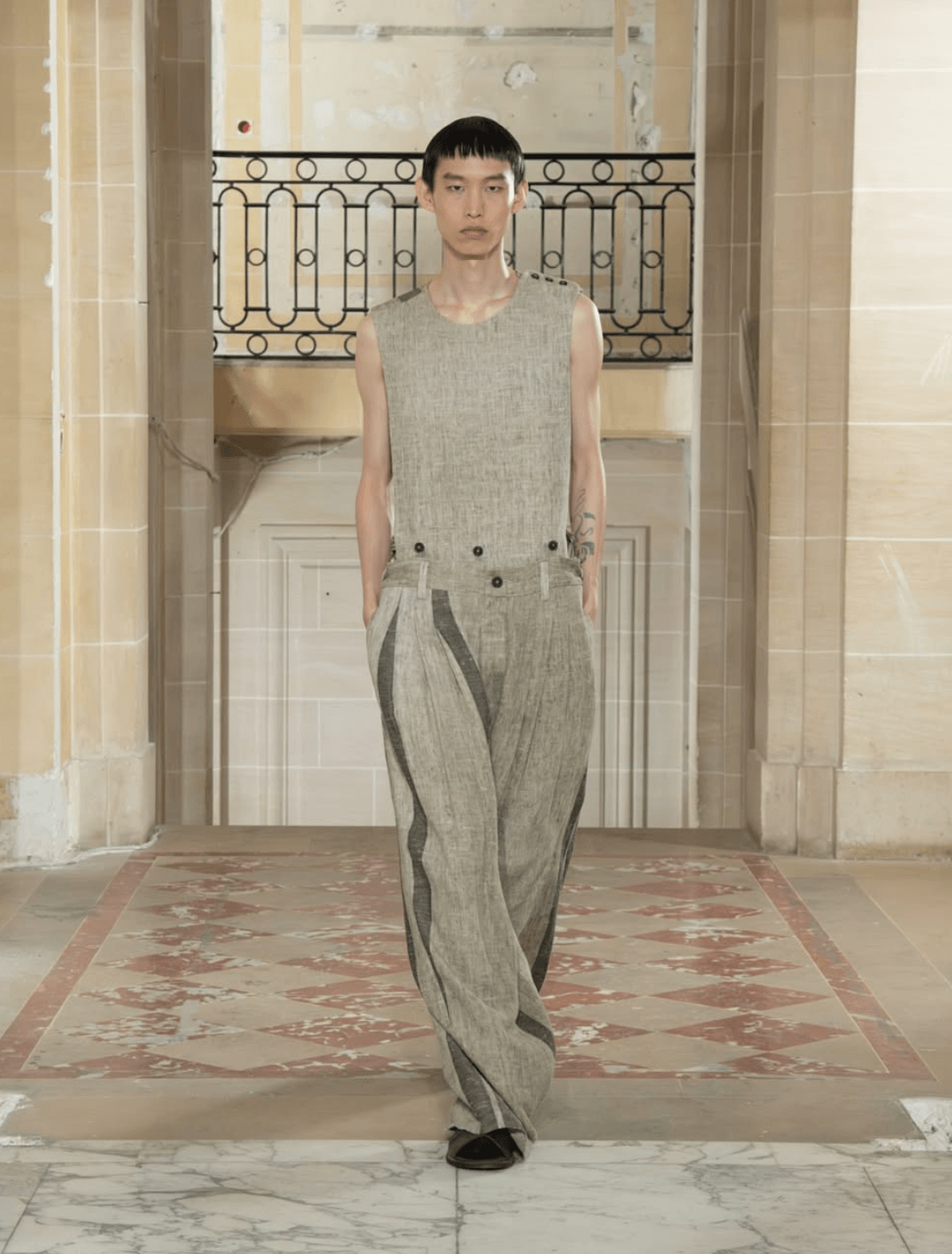

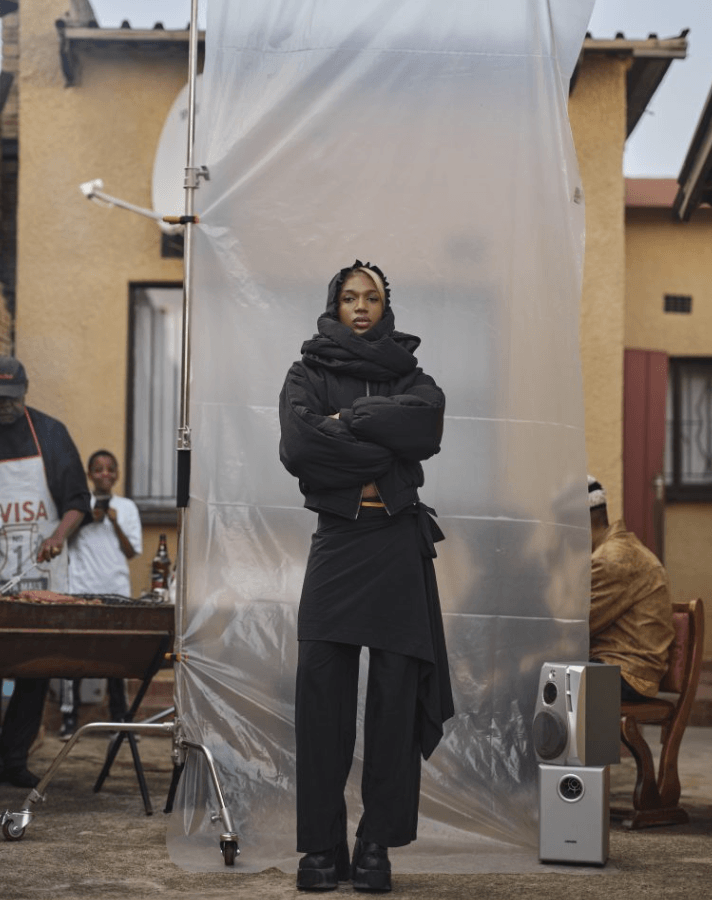

Initiated as part of Young Urbanists’ car-free street experiment, The MAAK and Faith Shields (‘Picnic’) hosted public sewing workshops in the middle of Bree Street every Sunday for two months. Along with hundreds of volunteers, donated materials were stitched into community-scale picnic blankets, reimagining the street as a shared, people-oriented space. Rooted in spatial typologies (kitchen, lounge, garden etc), and inspired by public prompts/input, different blankets were created to suggest unique urban activities. Some are stitched together with details to prompt movement or a specific action, while others invite reflection, pause or rest. In this way, the blankets are conceived as rooms without walls: an evolving floor plan that offers a new reading of the City’s surface—a coded landscape that encourages curiosity, interaction, and use.

“As strangers sat side-by-side, sewing and chatting, they slowly helped transform one of Cape Town’s busiest roads into a soft, shared community space. It was amazing to see fabric as both the material and the method to dream of a more welcoming, more human City for all.”– Max Melvill (The MAAK)

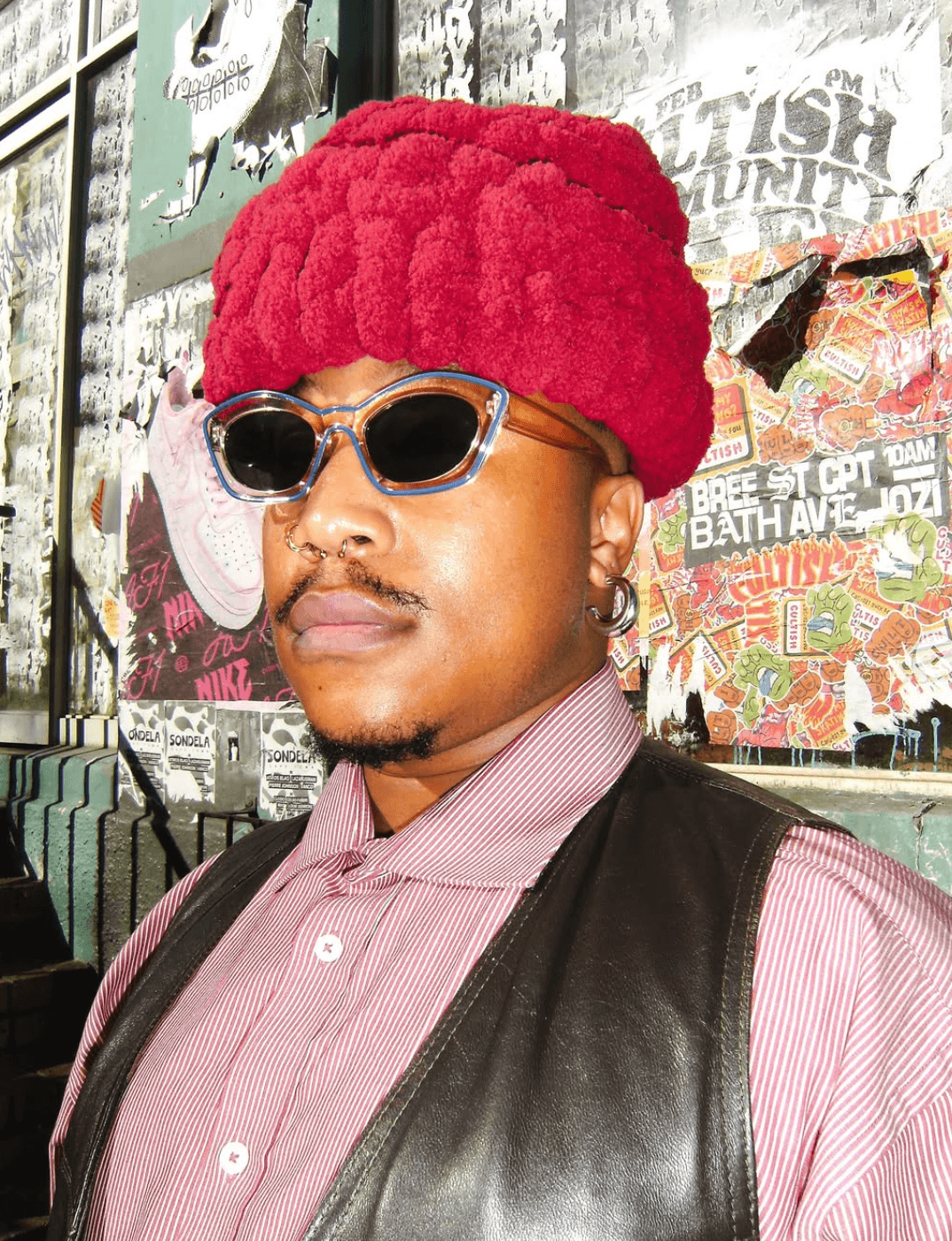

To celebrate the first phase of the project, the blankets were rolled out across the length of Bree Street for a giant public picnic, reclaiming the road as a fully pedestrian space. Local creatives were invited to activate each blanket in response to its spatial logic. Studio H co-created a 20-meter street sandwich with public participants from the ‘kitchen blanket’. The Jazz Cult performed live jazz from the ‘stage’, while modular seating and decor in the ‘living room’ was provided by artist Lebo Kekana x furniture designer N I S H and LOOKBOOK respectively.

“My experience of the project was that people felt safe and at ease breaking down any barriers for interaction and inviting people to step outside of the familiar and engage with broader community action. The different blankets helped facilitate this by providing unique and unexpected tools for public interaction: be it a dance floor, collective salad making or communal reading space.” – Faith Shields (Picnic)

Imagery courtesy of Picnic and The Maak

The softness and scale of the picnic blankets challenge the hard, exclusionary nature of car-centric urban environments and offer a more welcoming, human-centred alternative. In a country where access to quality public space remains deeply uneven and heavily policed, the act of being comfortable together in public becomes a powerful civic gesture. With this in mind, as the project—and the collection of blankets—continues to grow, like-minded collaborators are invited to use them to host further public events and community gatherings. Each new blanket activation serves as a simple yet radical proposition: that comfort, collectivity, and public joy matter.

About The MAAK

The MAAK is an award-winning architecture practice based in Cape Town, South Africa. Driven by process, people and materials the studio specialises in community, cultural and public-oriented projects. The MAAK was co-founded by Ashleigh Killa and Max Melvill in 2016.

Visit their website: www.themaak.co.za

Follow The Maak on Instagram: @the.maak

Press release courtesy of The Maak

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments