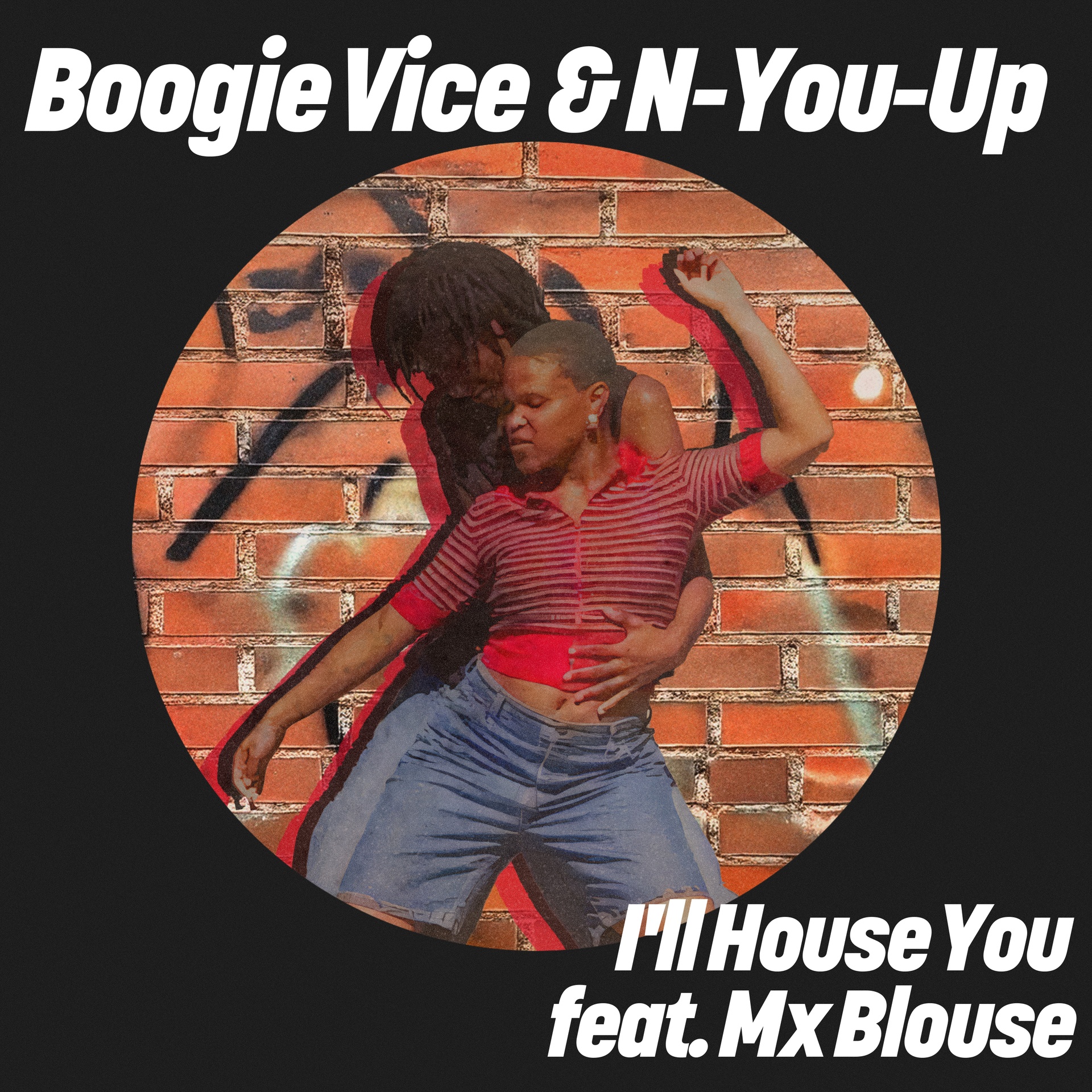

Boogie Vice, N-You-Up feat MX Blouse give us a modern rendition of Jungle Brothers’ ‘I’ll House You’

Boogie Vice, N-You-Up featuring Mx Blouse drop a cover version of an iconic Jungle Brothers tune. ‘I’ll House You’ is an enduring anthem that gets a modern update with three different mixes.

The Jungle Brothers dropped their legendary hip-house hit single ‘I’ll House You’ in 1988, and it became an instant classic, with their music paving the way for artists such as A Tribe Called Quest and De La Soul. Now, it has been reworked by South African musician and performing artist Mx Blouse, Parisian Boogie Vice and French electronic music producer N-You-Up for contemporary dance floors.

This innovative rework keeps the original Jungle Brothers vocals, which are full of house-funk attitude, but layers in a wonky melody line which slows the beats down and builds them into a low-slung groove. By listening, one can certainly hear how it seemingly fits into a nu-disco fusion genre. Raw percussive synths all help make this a notable rework that, with the standout vocals, may become an anthem in its own right. The tracklist includes a drumapella (acAPELLA with DRUM accents) version as well as a Dub Mix until finally, the Hope Street At Night mix is stripped right back to a shuffling and minimal groove.

Listen to ‘I’ll House You’ via Get Physical Music here

Tracklist

01 Boogie Vice, N-You-Up Feat. Mx Blouse – I’ll House You

02 Boogie Vice, N-You-Up Feat. Mx Blouse – I’ll House You (Drumapella)

03 Boogie Vice, N-You-Up Feat. Mx Blouse – I’ll House You (Dub Mix)

04 Boogie Vice, N-You-Up Feat. Mx Blouse – I’ll House You (Hope Street At Night Mix)

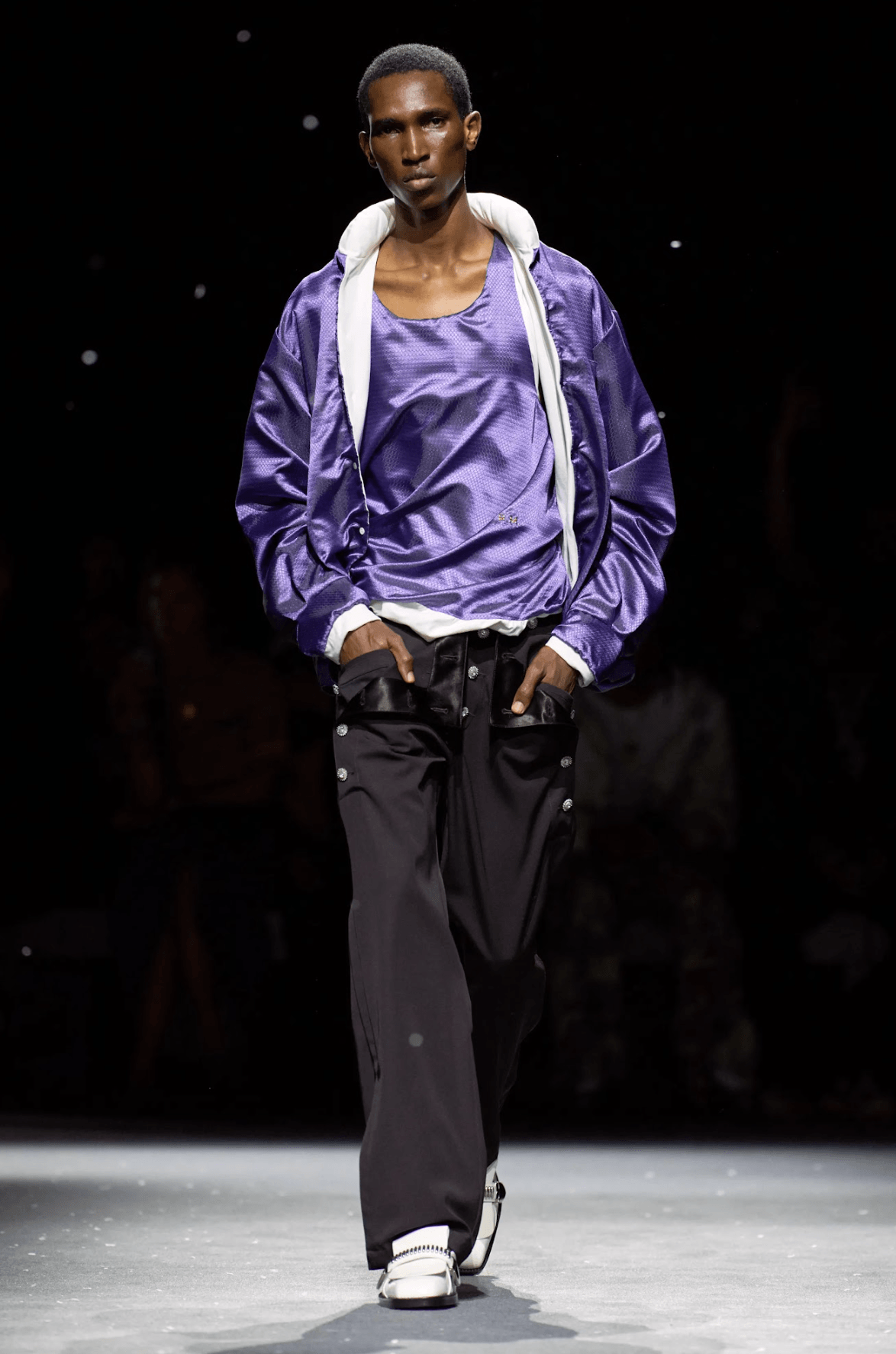

About Mx Blouse

No stranger to the CEC family, Mx Blouse is a genre-defying South African recording and performing artist. This is an artist who explores her creativity through music, spoken word, written word, and art direction. Read more about Mx Blouse here.

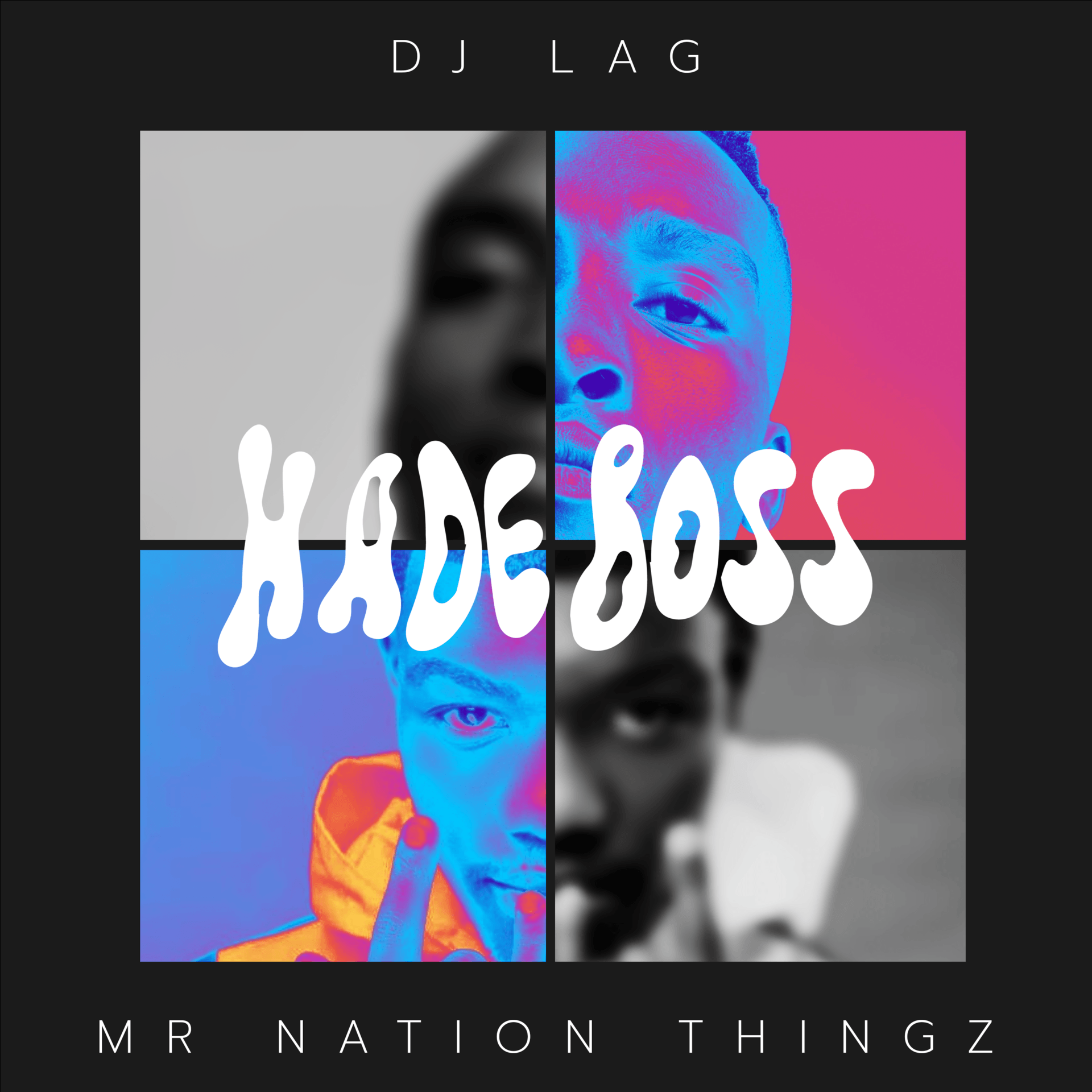

About Boogie Vice

Boogie Vice hails from Paris, and since debuting a decade ago, he has lit up Beatport charts, combining fresh nu-disco and house styles in unique ways and has released on the likes of Busy P’s Ed Banger Records, Amine Edge & DANCE’s Cuff and Miguel Campbell’s Outcross Records. He has previously released on this label alongside

Sensual Sounds head honcho Deep Aztec but now works with South of Fracas star N-You-Up. He has been DJing since 1996, first as hip-house artist The Beatangers, but with this alias returns to his roots and blends jazz, funk and disco on labels like Nervous Records as well as Get Physical Music.

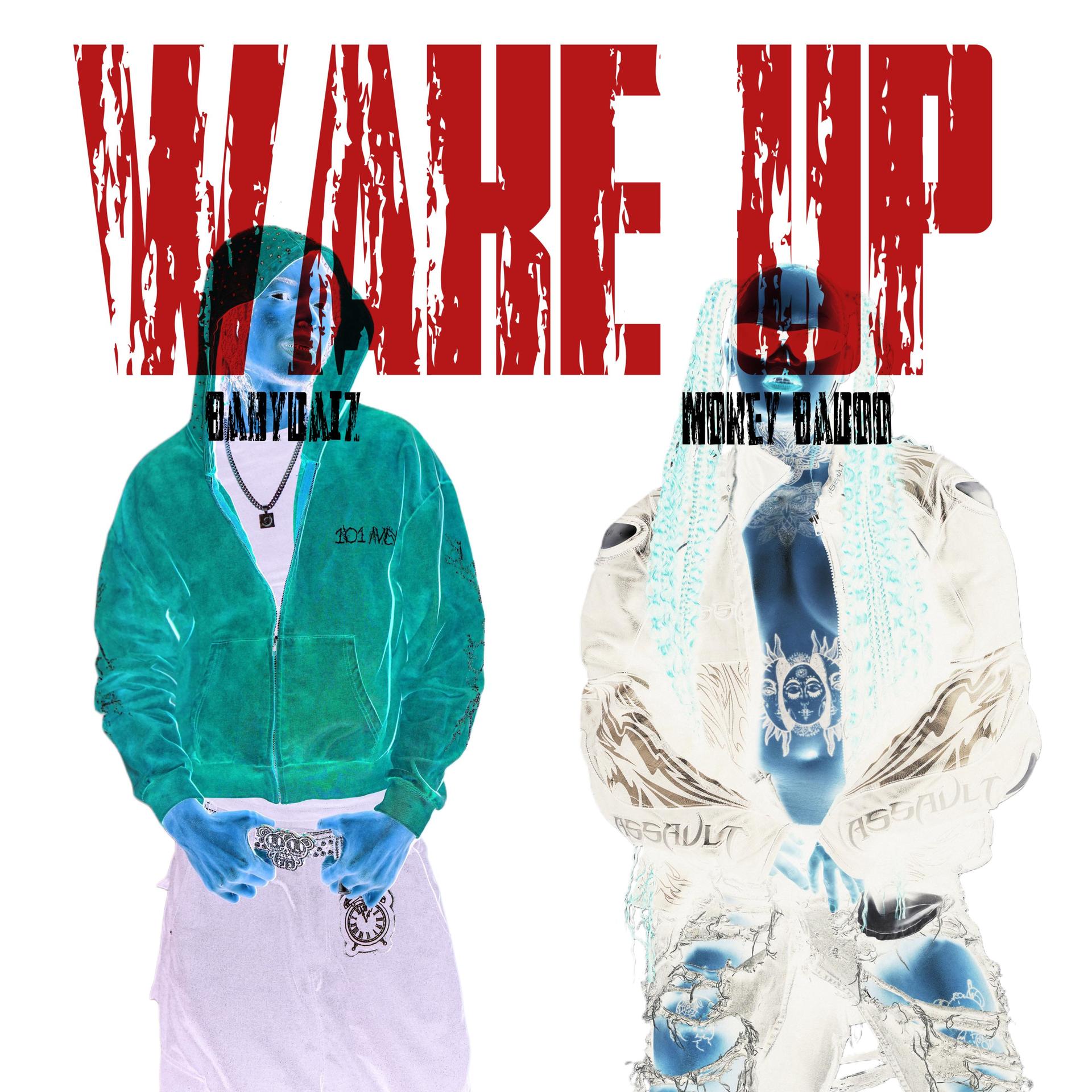

About N-You-Up

Southern France native, Nick aka N-YOU-UP is an electronic music producer. Nick’s love story with the dance floor served as the catalyst to jumpstart his DJ Career in 1996. His curated sets always aim to build a strong synergy with the crowd, while delivering his passion for music.

Follow Mx Blouse here

Follow Boogie Vice here

Follow N-You-Up here

Press release courtesy of Get Physical Music

Recent Comments