The Regenerative Vision of ArtAngels for Education, Creative Arts and Cultural Economy in South Africa

Every November, as the country exhales into graduation shows, year-end critiques and those last studio lights still burning late into the night, the South African art world returns its focus to nurturing education. ArtAngels is a regenerative micro-infrastructure built for artists and collectors, in a sector that has almost always had to invent its own scaffolding. In a landscape in which state cultural funding remains tenuous and artistic labour is consistently undervalued, ArtAngels has evolved over more than a decade into a circular system in which art sustains art, value circulates back into the community, and the future of the creative ecosystem is nurtured from within. In addition to this, a more hopeful vision of South Africa’s educational futures is made possible through the proceeds of ArtAngels.

When Nicola Harris first activated the inaugural event in 2012, it emerged from an observation about how the creative sector might support itself more intelligently. “At the time, Click Learning (the technology-driven literacy initiative which ArtAngels now sustains) was still new and I was still working at RMB,” she shares. “What I kept seeing was that people in those environments were incredibly willing to give, but time-poor. They wanted to contribute meaningfully but needed an avenue that made it simple and tangible. At the same time, my family has always had a deep connection to the arts, and I’d been dreaming about activating spaces like Circa in a way that felt alive and generous. ArtAngels was born from that nexus — bringing people with capacity into a room with good art and a clear purpose.”

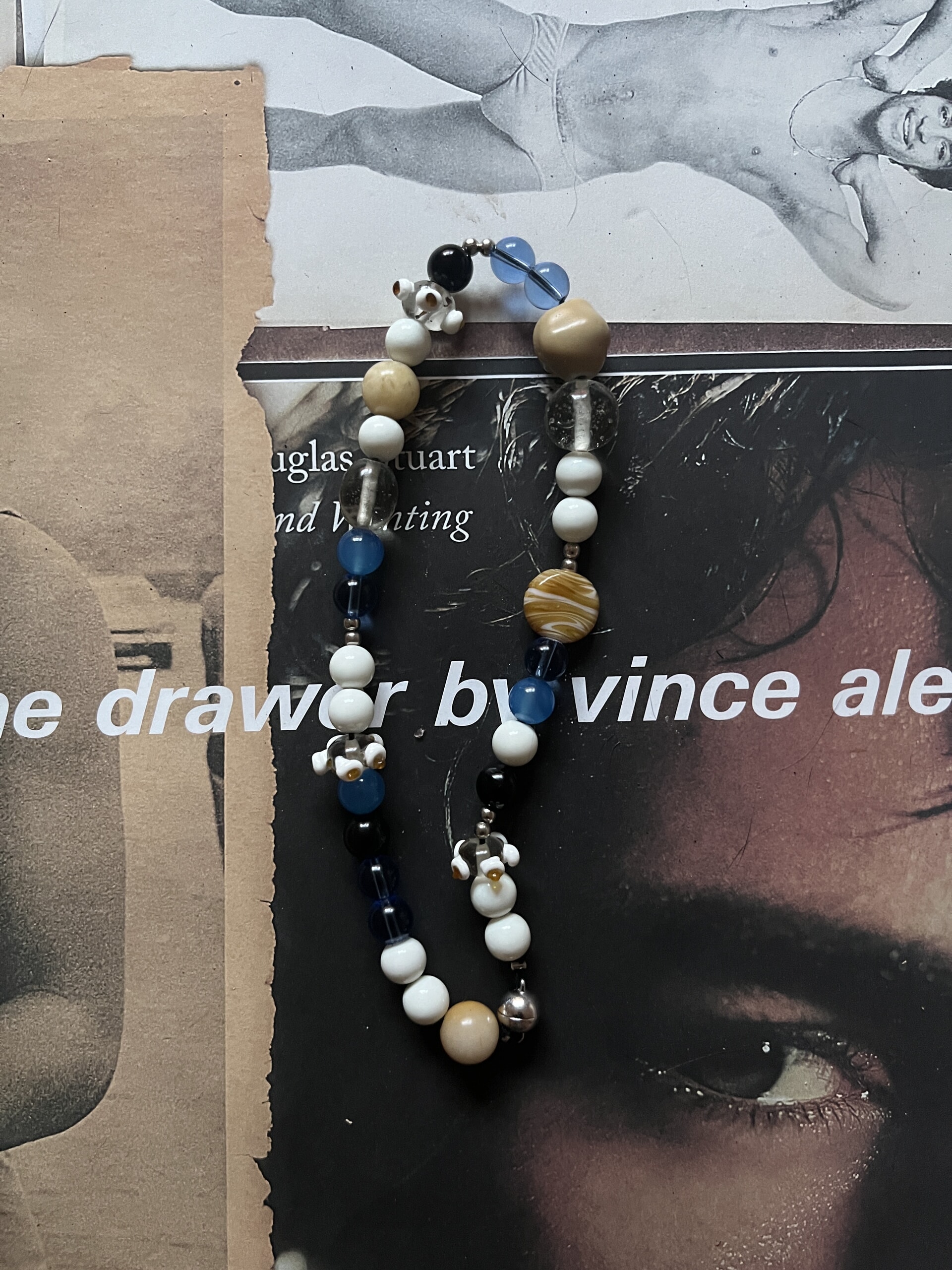

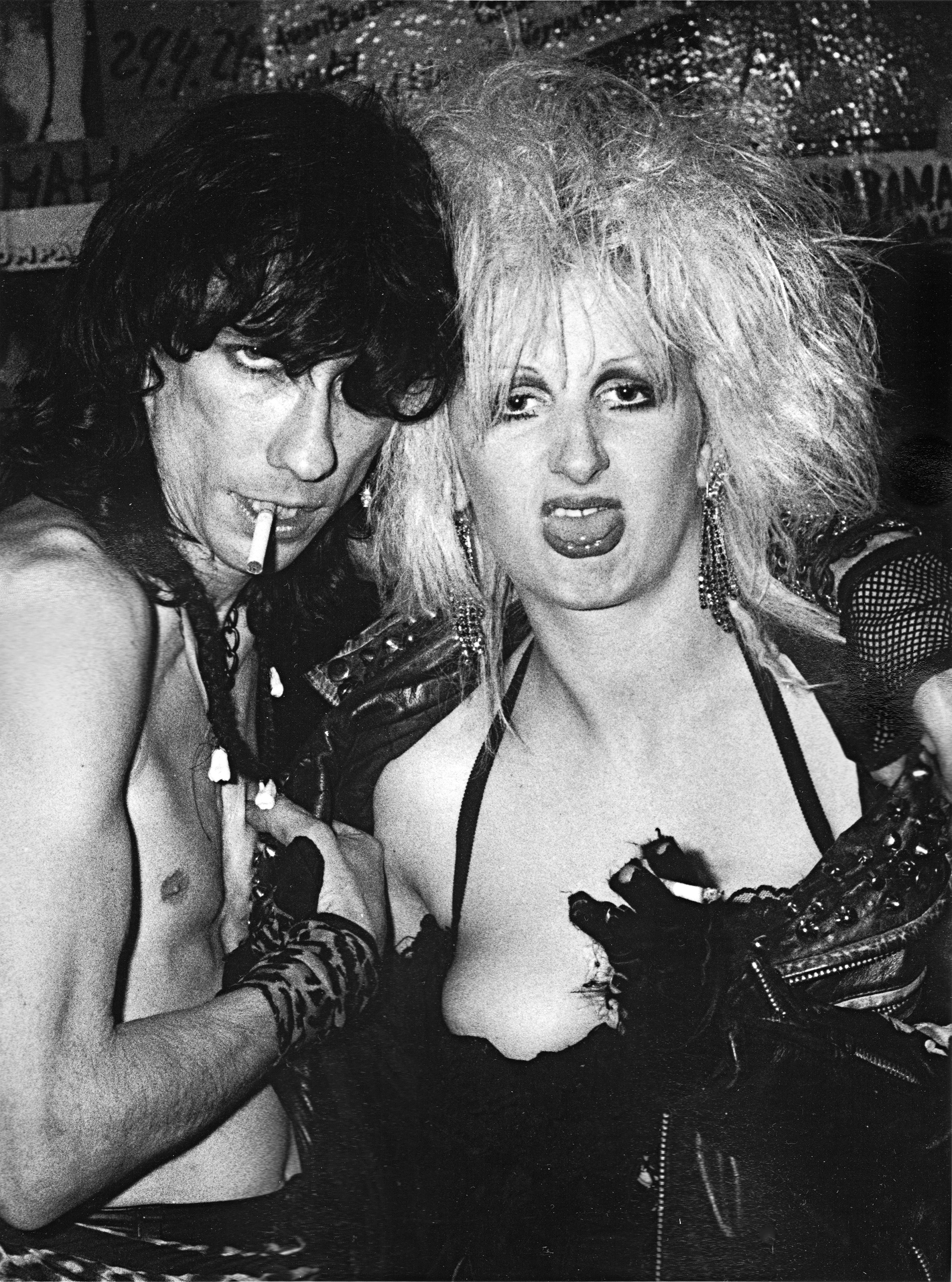

Artwork by Atang Tshikare. Imagery courtesy of ArtAngels

Artwork by Erin Chaplin. Imagery courtesy of ArtAngels

The purpose, however, has never centred solely on fundraising. From the start, Nicola and her team recognised a structural flaw in the traditional charity-auction model: artists are asked, repeatedly and relentlessly, to donate work, yet their contributions often sell below market value, undercutting both their income and their place in the broader ecosystem. As she explains, “In so many scenarios, artists are being asked to give something, but the event doesn’t extract the true value of their work. It isn’t great for the artist, it isn’t great for the beneficiary, and even for collectors it undermines the value of these artists in their collections. The value proposition we offered was simple: if you’re willing to give, let us create a forum where that generosity can actually be maximised, for everyone involved.”

The philosophical shift embedded in ArtAngels became most apparent when Harris introduced the now-well-known 10% commission for contributing artists — a gesture small in percentage but immense in meaning. It recognises that donating a work is the giving away of income, labour, hours, material costs and creative energy that cannot be recouped. “We realised it was a big donation from the artists, especially younger artists,” Nicola notes. “So acknowledging that, and giving them something back, meant they could offer strong works rather than whatever was left in the storeroom. It’s worked incredibly well. Everybody gets to contribute high-quality pieces, and the whole ecosystem benefits.”

It is precisely because ArtAngels places artistic labour at the centre of its philosophy, that the event has slowly become one of the few annual moments where the South African art community gathers across generations, galleries and practices in a spirit of collaboration rather than competition. “I don’t think the arts community often has an occasion where painters, sculptors, photographers and gallerists all come together to connect, celebrate and rally behind a single cause,” Nicola reflects. “It creates a real sense of community — and for buyers, it’s a rare opportunity to engage with that world in a way that feels intimate and joyful.”

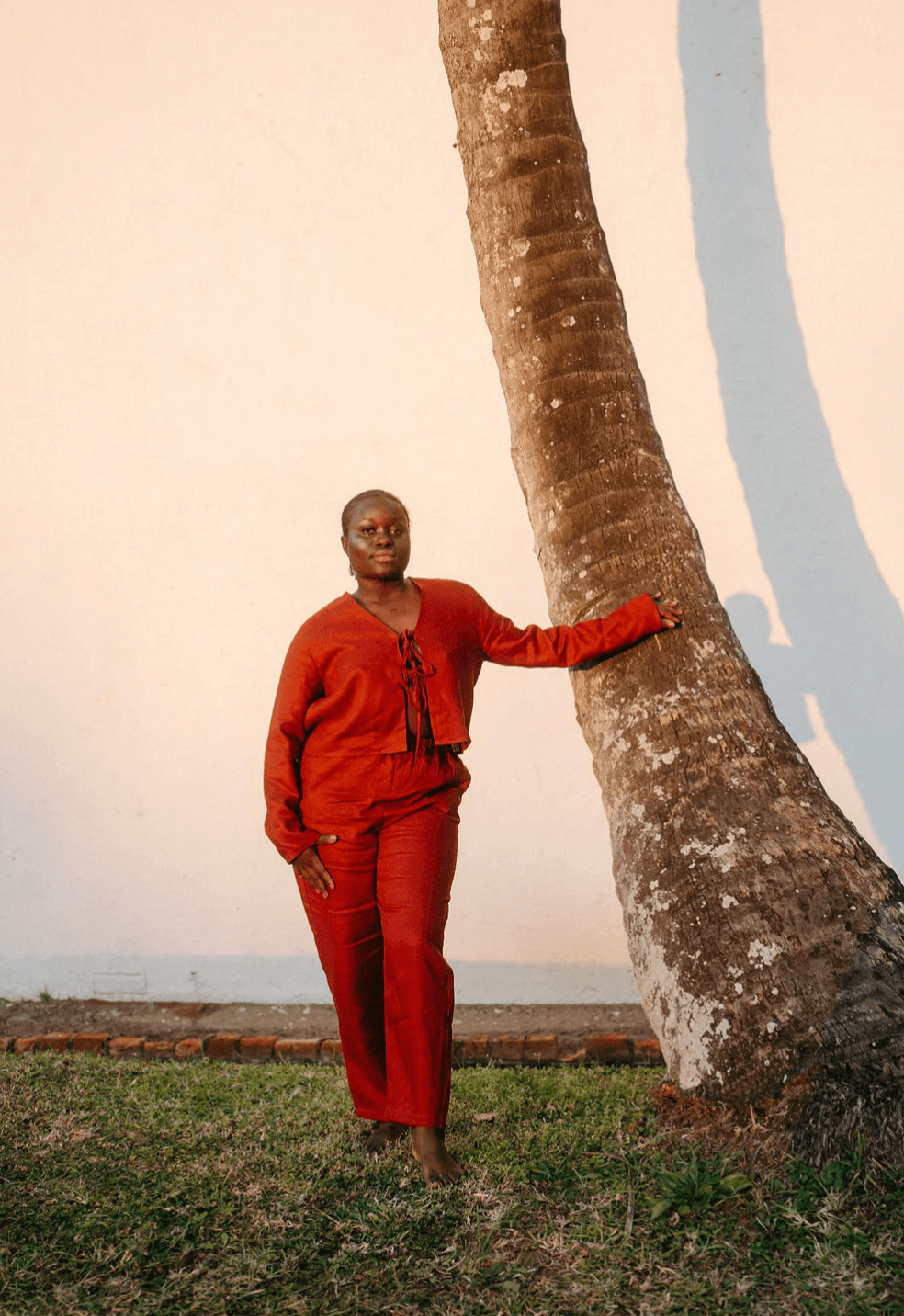

Artwork by Dada Khanyisa. All imagery courtesy of ArtAngels

Artwork by TERESA KUTALA FIRMINO. All imagery courtesy of ArtAngels

This sense of circulation — of value moving through the ecosystem and returning to its source — extends into the ways ArtAngels reinvests in future creative talent. Ten percent of net proceeds (after direct costs and artists commissions) now fund the Blessing Ngobeni Art Prize, scholarships at Ruth Prowse School of Art, and other development pathways that feed directly back into the system. “It is important for us to give back into the arts themselves,” Nicola explained. “Especially because the arts are also profoundly under-resourced. It’s become a full-circle for us, the arts sustaining education, and education sustaining the arts.”

That same circular logic animates Click Learning, the parallel project Harris founded the same year, which uses technology to radically personalise foundational learning for South African children. Nicola’s commitment to Click Learning is underpinned as a system of circulation in which knowledge, agency and future possibility can be advanced. “Technology allows us to meet learners where they are,” she says. “It doesn’t matter if a child is ahead, on track, or far behind. Personalised learning gives them exactly what they need at their own pace. We know that foundational literacy and numeracy is the key building block. It’s the strongest predictor of future academic success and employability. Ultimately, we want young people to stand on their own feet with dignity.”

Today, Click Learning operates in 316 schools and reaches over 230,000 learners. “Our grade four and five learners in the Eastern Cape, who spend just two hours a week on our programme, are performing four times better than those without the intervention,” she shares. “ArtAngels was crucial in those early years. It gave us the freedom to experiment and innovate before we had proof. It allowed us to break the barriers that always arise in education.”

This year’s edition of ArtAngels was its most successful yet — more than nine million rand net in funding distributed directly to beneficiaries — and the energy of the night, as Nicola muses, also revealed the art world’s growing interdependence. New galleries joined alongside long-standing participants, a number of first-time buyers appeared on the acquisition lists; and Strauss & Co’s involvement expanded the online reach, bringing international bidders into the fold. Most striking of all was the work produced by bursary students and previous prize recipients: strong enough to hold its own in a room of established artists, confident enough to earn real bids. “Seeing these works stand confidently alongside established names is incredibly exciting,” Nicola says, “It’s a glimpse of the full circle — talent nurtured through the ecosystem returning to nourish it.”

In a year in which much of our cultural infrastructure feels stretched thin, events like ArtAngels remind us that the South African art world survives by designing its own systems; subtle structures built from resources, collaboration, reciprocity and mutual faith. ArtAngels offers a model for what cultural and creative resilience can look like in a country that has always created more than it has been given.

Written by Holly Beaton

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments