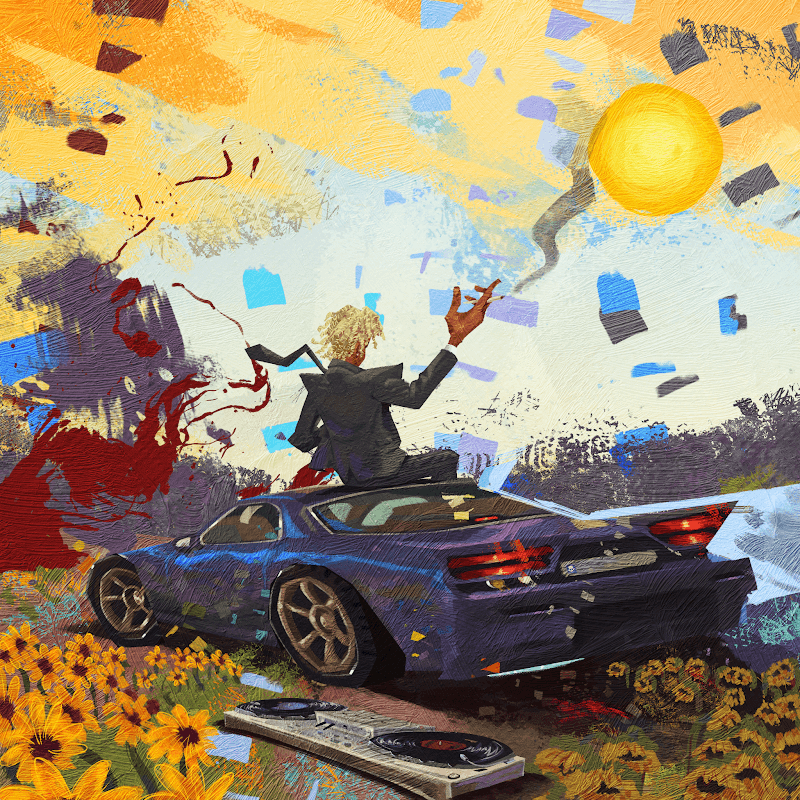

Amapiano Innovator Ch’cco Explores The Evolution of Pitori Culture Alongside Focalistic With Their Collaboration Album ‘B.O.A.T.S.’

Linguistically, my contemporaries would posit that the terms “From nothing to something” and “the come up”, essentially borrowed from the Hip-Hop fraternity, have evolved into a rags-to-riches branding rhetoric, giving credence to the credibility of the modern icon. We may have lost touch with the essence of what those phrases mean to those who echo them. Creativity birthed from circumstance, often the rebellion against poverty and the status quo has curated some of the most memorable mediums of craft that reverb through museums and stadiums; giving the perception of the audience a sight to behold, a thought to chew on, a sound to work through or escape adversity and in the process of overcoming – communicating not only the tone of pop-culture, but the philosophy of precisely what is possible.

Shiko Goodman Matlebjane, affectionately known as Ch’cco, reverberates the spirit of creative nonconformity. Born in Limpopo, raised in Pimville, Soweto, and spending the better half of his life in Mamelodi, Pretoria, his artistry embodies a multi-platinum-selling enclave of being in tune with the pulse of the streets and forging a path, setting the stage for the next chapter of the evolving sonic tale of South Africa. Consider the layers of pioneers that he shares a common thread with, including the post-apartheid renaissance of Kwaito, Deep House, Tribal House, South African Hip-Hop, Gqom, Afro-Tech, and the first wave of Ampanio and 3-step, to name a few. At some point, these styles of music were counterculture, then they became the profitable formulaic status quo. This often pushes the artist into a crossroads where they either become pigeonholed into what they are popular for or they gamble with every stage of their evolution and advance the culture forward.

As an acclaimed lyricist, producer, and style maven, he has been an advocate for staying ahead of the curve since his days of storing songs on Nokia 3310 voicemails. His rise to prominence is intimately tied to the culmination of his latest album, B.O.A.T.S, a vast celebration of community and his collaboration with President Ya Strata and Focalistic.

‘Based On A True Story’ walks in the lineage of elements tied to the acclaimed Pitori Super League — a collective composed of Focalistic, Pabi Cooper, Mellow & Sleazy, M.J. and other talented Pretoria artists. While not formally a record label, the movement has represented the Pitori ethos with lauded blockbuster chart-toppers, namely Ch’cco’s breakout singles “Nkao Ntempela” and “Pele Pele”.

Complemented by astronomical streams and Spotify playlist covers for Amapiano Groove and New Music Friday respectively, B.O.A.T.S. epitomises the spirit of paying it forward. Similarly to how Mellow & Sleazy discovered Ch’cco online, Ch’cco & Focalistic paid it forward by introducing producers like Sims Noreng, who were discovered on social media.

Imagery by Hayani Africa

Image Credit Mishaal Gangaram

Meditating on the power of social media and divine alignment, Ch’cco ruminates: “Realistically, we never put ourselves in a situation where we’re outsourcing producers. It’s just been a product of God’s blessings, aligning the right people, time and place. Usually, we meet on Instagram. We’re like, “Yo, I like what I’m hearing. Let’s put it to the test. Let’s take it to the studio.” When we get to the studio, we experiment and do more.”

B.O.A.T.S, in the larger rags to enriching the culture conversation, puts Ch’cco at the forefront of challenging the framework of what Amapiano can be, the Hybrid movement encapsulated in this album piqued my Kasi flair, sparking a conversation about the PSL, his role as a team player, “31314” and his future plans.

Steam “31314 (Interlude)” here

For our readers who may not be familiar with you, could you please introduce yourself? What was the most unexpected element of your journey into music?

Ch’cco: “Sho, Dintsang! Shiko Goodman Matlebjane here, I go by the name Ch’cco. Born in Limpopo, raised in Soweto, and grew up in Pretoria. I’ve loved music for as long as I can remember. I was introduced to this whole universe by my late father, Opa France Matani. But honestly, it’s just something that’s been in the family. My grandmother is the pioneer of it all; every Sunday, we’d be bumping tunes that she was playing. It just rubbed off on everyone in the family, really.

Music is my true self, my true form, my true personality. There’s only so much I can say in words; most of it is in the records that I produce. My upbringing helped me understand craftsmanship from early on and showed me the diverse directions my sound as a language can take. The challenge has always been incorporating how diverse everything already has been for me and communicating that to the world. But I’ve always looked at it as an advantage, to say the least. Music is a universal language, yes, but there are still language barriers to overcome.

Being blessed enough to grow up in different environments enabled me, over time, to connect with people on a personal level, particularly in terms of communication, where clarity is key, allowing us to hear each other clearly and effectively. That’s always been my ongoing objective throughout my career: finding a way to connect everyone from everywhere with this one specific thing.

“Haena Wrongo” is a perfect celebration of the ongoing chemistry of the Pitori Super League movement. How do you maintain that artistic and cultural integrity amidst the growing success you experience individually?

Ch’cco: “It’s the love we share for each other and the music we make, how we connect in the studio. It’s really that simple. It’s by far the easiest thing I’ve ever done, making music as PSL. You’re already set up for success. You already know what you’re going to get: the lovely Papi Cooper on vocals, Focalistic with his raps. On a good day, if you get production from me and Sleazy, it’s a bonus. In this case, though, we had Young Sims Loreng, a special guy to look out for.

He’s a young but highly talented man. He wrote four songs for the album. PSL is truly a sacred movement, especially as we watch it mature and see how we’re growing within it. We’re better than we were the day before, as far as the music is concerned. Every record serves as a prelude to a better one, so it’s really exciting to see it turn out the way we planned. The growth is something I’ll continue to highlight; it’s extremely exponential. That’s really something to put up there as far as the things we cherish the most.”

“B.O.A.T.S” also reveals you as a team player, knowing when to grace a song with your artistry and when to make space for collaborators to shine. Did this album teach you the art of being a producer and curator in a sense?

Ch’cco: “100%. It taught me the art of balance, particularly when working with people, such as collaborating with someone as accomplished as Focalistic. You’d think it’s simple and free-flowing, but there’s so much that goes into it. You also learn a great deal about the seriousness with which they approach their craft and their business.

“B.O.A.T.S” as a project, I feel like there were a whole lot of things that were learned, not just by me but even by the audience, about how an album is treated and created. To such an extent, it will continue to appear in my future works of art. It’s something we rarely discuss. We shy away from it quite a lot because we’re not ones to toot our own horns much. However, as far as a rollout is concerned, this is one of the best rollouts I’ve seen for any album in the history of South African music. So, it truly is something to be embraced.

Definitely, I’ll see myself implementing many of the things I’ve learned, even as a producer. You highlight the fact that I’m a team player, but I never thought of myself that way. But it actually showed me how much of a team player everyone involved in the body of work was. I don’t believe the success of the project would have been what it was if it weren’t for the likes of Sims Noreng, myself, all the other producers, all the managers who were involved in creating the shows and aligning the deals, the people who are actually making this interview for you and me to speak right now. It’s an extended effort of what we’re essentially doing here.”

Image Credit Mishaal Gangaram

Imagery by Hayani Africa

I effortlessly gravitated towards “DropTop” and “26 Nights” with their ease, charisma, and flair. Could you walk me through the art of crafting elements like setting the mood, flow, and style for those songs? How does working with DJ Maphorisa affect your approach?

Ch’cco: “You know, those songs, those types of sounds where we’re rapping and trapping on top of is’gubhu, I think those will always be the easiest songs for us to make. That’s really just another day for us with Mellow & Sleazy. Seeing Mr. Pilato rock, they just stay in my room with Ego Slim Flow, Tebogo, Koki and fellow creatives to keep the momentum going. And when we’re in the studio with Foca still there, it was just another free flow. As far as the legendary Phori is concerned, that was long overdue for us to have an official record out there. But as far as learning from him, I’ve always been blessed enough to be in spaces where he was; he’s actually a very insightful person.

There’s no way you’d spend time with him or be around him and not learn unless you’re not that type of person who likes learning. But there’s no way you wouldn’t absorb some significant new information. I’ve always been honoured to be in similar spaces with him from time to time, and we’ve actually worked on a lot more songs than just this one specific one. However, this is the one that saw the light of day. Those trappy songs will always be in our pocket, believe us. That’s why no one will even try us in that sense. But I’ll say, you know, it’s tough to be this dope, but somebody’s got to do it.”

Thank you for coming to our interview. Before you leave, could you tell us what the future holds for Ch’cco?

Ch’cco: “‘B.O.A.T.S‘ is a timeless body of work, so I don’t think I can ever tell you what’s next or when it’s going to end. It’s just going to keep going. We can drop a music video in four years because we just feel like it, that’s the chemistry. We spoke of deluxes, we spoke of a whole lot of things, but once we actually start actioning it, the streets will know that it’s real. The visuals will definitely be there.

The whole country wants to see a music video for PSL. Focalistic, Pabi and I, although we share several cameos for each other in our respective music videos and social media, we still haven’t created a beautiful video together for the body of work. So that one is highly anticipated. “31314 (Interlude),” the prelude to the actual album, has also been taking shape in the B.O.A.T.S sessions.

Every song in the album is an experiment, We selected 12 within over 26 phenomenal songs, that were being treated and the stakes are higher for me because with my forthcoming debut album, I’m part of the sport, you’re dancing between negotiating for those songs to be on the album or making songs on the album that can compete artistically with the infectious energy present. I’m eager to share the album with my community. It’s been a long time coming. I’m looking forward to releasing more music and collaborations.”

Stream ‘B.O.A.T.S’ here.

Connect With Ch’cco

Instagram: @chiccoalot

X (formerly Twitter): @chiccoalot

Tik Tok: @chiccoalot

YouTube: @chiccoalot

Written by Cedric Dladla

For more news, visit the Connect Everything Collective homepage www.ceconline.co.za

Recent Comments