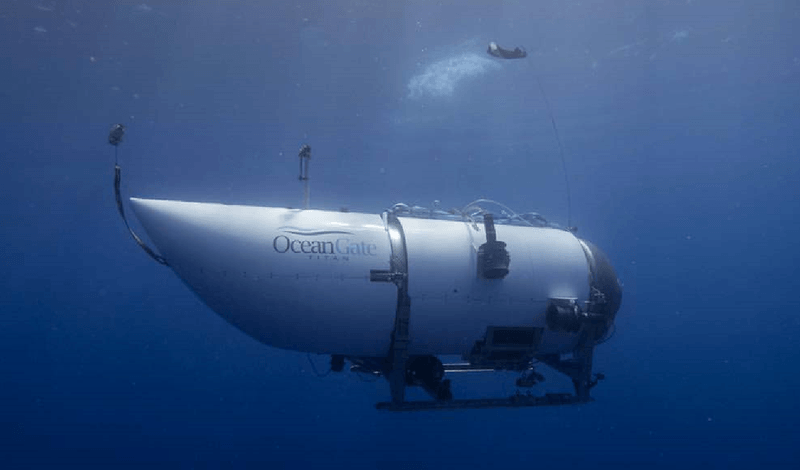

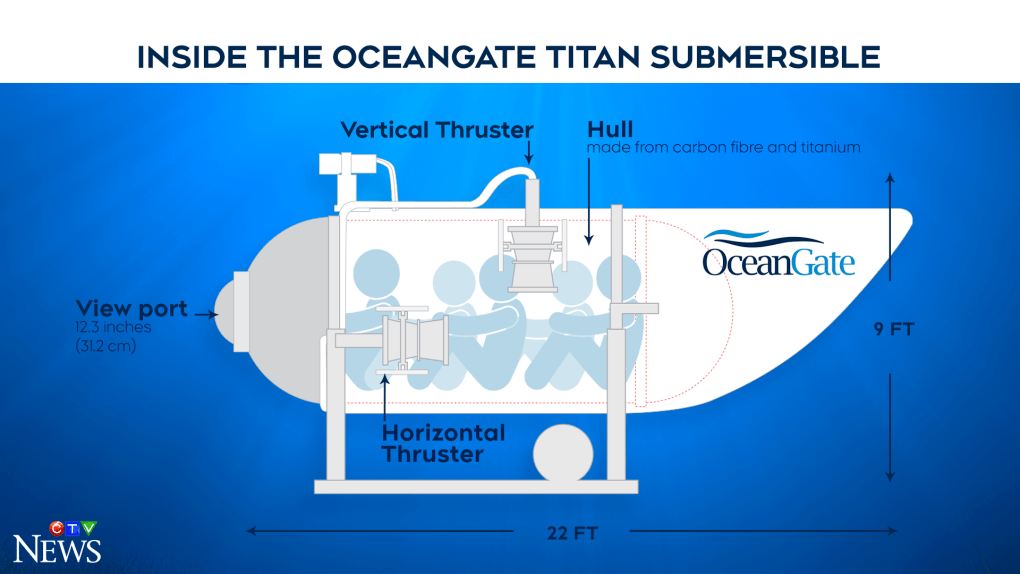

More people have explored space than the depth of our oceans and pressure is one of the key reasons as to why this is. Water pressure increases deeper in the ocean due to the weight of the water above it. This pressure, known as hydrostatic pressure, is a result of the force exerted by the weight of the water column. As you descend deeper, the weight of the water above adds up, causing an increase in pressure. Typically, the hull of a deep-diving submarine takes on a spherical shape to ensure uniform pressure distribution across its surface. In the case of Titan, its hull was a cylindrical ‘tube-like’ shape, causing an uneven distribution of pressure. Stockton Rush, the CEO and designer of the submersible, negated every single piece of professional evaluation and advice he received by experts on this design.

This is one of the reasons why the submarine was not able to be certified, as the Titan was deemed unconventional and deviated from the established standards. However, Stockton Rush emphasised that this did not imply that OceanGate failed to meet the required standards in any relevant areas and that classification agencies hinder innovation through their stringent measures. Such is the hubris of a billionaire who thought that a spherical ‘tube’ – despite its lack of structural integrity for the purposes of pressure distribution – was in any way, innovative.

The vessel weighing 10,000 kgs was constructed using a combination of “titanium and filament wound carbon fibre.” Ocean Gate claimed that the vessel had been extensively tested and proven to be a secure and comfortable means of transportation capable of enduring the immense pressures found in the deep ocean. While carbon fibre has been widely utilised in the aerospace industry, its ability to withstand the repetitive deep-sea pressures had not been conclusively established. The Titanic wreckage rests at a depth of approximately 4000 metres, significantly surpassing the typical diving range of the U.S. Navy submarines, which usually descend to depths of around 600 to 900 metres. With that, the use of mixed, experimental materials were also at a risk of expanding and contracting at different temperature and pressure levels – in and of itself, a major risk to the structural integrity.

While tragedy is never a welcomed thing, and five people lost their lives; the most enlightening discourse arising out of this matter is the seeming arrogance of a billionaire like Stockton Rush, who truly believed that his design was not only safe enough to reach the Titanic wreckage; but that charging $250,000 for commercial use and inviting clients to sign death waivers, was a good idea. This avoidable, albeit totally accidental, disaster has cost millions of dollars and compelled the attention of the world, and seems to showcase the time and attention afforded to billionaires seeking ‘thrill’ and adventure, over a humanitarian crisis such as the capsizing of a refugee boat, which was worryingly mishandled by the Greek Coast Guard. Since the early 2010s, there has been a prominent and ongoing humanitarian challenge involving irregular migration and dangerous voyages undertaken by refugees and migrants across the Mediterranean Sea, primarily from North Africa and the Middle East to Europe. This crisis is fueled by a range of factors, including armed conflicts, political instability, human rights violations, poverty, and limited opportunities in their home countries. Desperate for safety and improved lives, refugees and migrants frequently embark on hazardous journeys aboard overcrowded and unsafe boats, often with the help of human smugglers.

We live in a world where the lives and longevity of the very wealthy (from celebrities to tech gurus, to politicians and so on) are more important than the majority of the world. In a classist, divided world; poor people, fleeing in fear from their homeland due to geopolitical instability, just doesn’t get quite the same airtime as five consenting billionaires who thought a one-trick-pony of a submarine was the best route to seeing a wreckage that is over a hundred years old. I suppose when you have the world at your fingertips, such indulgences are par for the course – and what does 500 human lives and counting, such as with the recent migrant boat disaster, mean in any way? Well, it’s clear what it means: the coverage of this story and the millions injected into it, are directly proportional to the continued devaluation of everyday people.

Recent Comments